|

|

Unka

Kim's

Martial Art

bloggie thingie

|

|

If

you'd like

to comment on anything

send us an email |

You can track this page with Google reader, firefox add-on

Update Scanner or others Click

here for info

Follow SDKsupplies.com at:

|

|

|

|

Theory

|

Brutal Self Analysis

These notes aren't so much the crabby natterings of Unka Grumpy, as a

dialog with myself and those six readers who bother with them. As I

write on this or that I find what I think about the topic. This may

sound strange, after all, how can you not know how you think? Trust me,

if you accept the first reaction to a question you are, by definition,

not thinking, you're "going on instinct"

which means you are using prejudice and dogma. Granted, it's easier to

simply "stick to your principles" and repeat the beliefs by rote, but

any opinion that can't be examined and defended, modified and amended is

just that, a belief system. The world is not flat and DNA exists, I

know that because I've seen the world from high up and I've made new

things from DNA for a living.

You have to examing your

"beliefs" as rigorously as you practice your martial arts. Your thoughts

must be organized like you organize your kata or you will ever be a

beginner, an uneducated child in the universe of knowledge. The first

step is to accept that what you know may not be what is true. When you

practice the sword, your first step to improving, to living through the

next battle (let's assume you fall through the Alternate Universe

Interface and need to fight the zombies) is to hand yourself to a

teacher. What this means is that you simply listen with an open mind so

that when your teacher says "your tip is low" you do not accept your

first body impression and deny it, but you question your propioreception

and accept the possibilty that you may be mistaken about where you

figure the tip is. Raise the tip and look at the mirror (not the other

way around), or raise the tip until teacher says OK, then tell yourself

the tip way up high like that isn't really way up high. Eventually, if

you're a good student willing to question your own body sense, you will

come to believe that feeling is the correct position. You will come,

through questioning and an open mind, to a true feeling for the tip of

the sword.

Who is the teacher in your mental journey to truth?

Well it isn't a book, it isn't a teacher who makes you memorize the

times tables or repeat historical dates. It isn't dogma we're looking

for, it's truth, and while dogma may sometimes be true, it can't by

definition (dogma doesn't change), become true. Facts and figures are

not truth, the search is truth, the question is truth the start and

finish is theory. This is "science". The scientific method starts with

an idea, just like religion, but science means you try to disprove that

idea. You question, you experiment, you measure and you stress test.

When your discussions and investigations show cracks in your idea, you

change the idea and start the process once more. This continues for your

whole life, the process being the important part, just like swinging

the sword is the important part, not getting the grade or having the

fancy title. You can self-award a rank and you can come up with amazing

ideas but both are delusion. Even coming up with a "true" idea is

delusion until you test it, accidental truth isn't any more useful to

your growth than thinking up fairies to explain mood swings. Being open

to changing your mind, or changing your propioreception is not

"betraying your principles", it's having a student's mind (shoshin).

Without shoshin learning is impossible.

Without putting your

beliefs and opinions out there so that someone can get in your face and

call bullshit, you have no shoshin. It's a bit distressing that in the

"age of the internet" where we can reach people all over the world, we

seem not to be seeking conflict, but rather we create bubbles of

confirmation. We split up into groups and subgroups who agree with us

and stick to them. It's rather like when the library got rid of the card

catalogue and went digital, suddenly I wasn't seeing all these

delightful titles that were close in spelling to what I wanted, but far

away in topic. Computers meant a restriction of experience, a loss of

the wild idea coming in from left field.

Next time you do

something that doesn't make sense, do a little brutal self-analysis and

figure out why you did it. Keep questioning, keep growing.

Let yourself be taught and you may survive the next zombie invasion.

|

June 30, 2013

|

Technique

|

What's the New Footwork on Ushiro

Got that question from someone recently, seems he's heard about an

"advanced" way of turning in Ushiro and wants to know all about it.

Thing is, there isn't a new way of turning, but in the ZKR iai

committee meeting of 2010 it was accepted that two ways of turning were

acceptable. One is to rise and tuck the toes under then turn. The other

way is to roll the left foot over

somewhat as is done in MJER koryu. This rolling over of the foot was

always introduced as an advanced way of turning, being a problem for Zen

Ken Ren iai beginners. Now... I teach it to MJER beginners in Seidokai

because it really isn't hard when you are turning to face an opponent

at ma ushiro, directly behind. One takes the right knee to the left,

then moves forward with the right knee so that it moves in front of the

left and receives the body weight, which means the left foot is very

light and can roll over easily.

ZKR Seitei Gata Iai is

different, the important point in this school is not to face an opponent

directly behind, but to face an opponent to the right rear, and

explicitly to move the left foot to the left on the nuki tsuke cut. The

right knee stays in one spot and it's hard to shift the body weight onto

that knee without looking like a pine tree in the wind (matsu kaze as

it were). To make this left foot movement clear, we teach beginners to

tuck the toes under which makes the turn and the shift easier (clearer)

than using the koryu way of turning. When students get to about 6dan we

tell them they can do the turn MJER style and they can roll the foot if

they wish. I should say here that I don't do ZKR iai this way unless

I'm demonstrating it, I tuck the toes under because this makes the most

sense to me, especially with my damaged knees.

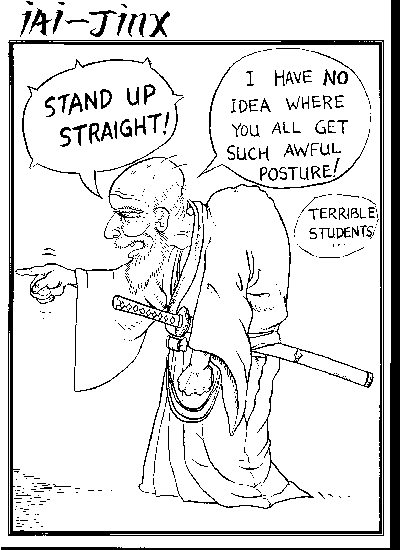

Unfortunately,

the word has got out and now the nidans want to do it the "advanced"

way. Anyone with a little bit of experience, as in maybe a month, wants

to do the "advanced" stuff, it's only natural. And now I'm going to have

to start dinging grading challengers for not moving their feet since

the rollover usually pushes the left foot out before it should go.

Folks, at 30 years worth of practice, I can tell you that you should be

looking for the "basic" way to do things, not the "advanced". Resist

the "advanced" way for as long as you can because that way you can show

the best iaido. Let me explain this another way. At first kyu and shodan

we allow students to pick any 5 kata they wish. There are some

students who pick the 5 they are most confident with (and they are

always the most basic kata, the "simplest") and some students who pick

the most "advanced" kata, the ones with lots of moves.

The

"basic" group get it. As a judge I want to see your basics, I want to

see that you understand "free choice" means we want you to show us your

best. The "advanced kata" group inevitably figures that we give bonus

points for knowing the footwork to the complicated kata. Unfortunately,

there are only 12 kata in total and I've seen all of them thousands of

times, with some of those demonstrations coming from people who are

really good. At shodan you are not going to impress me by knowing the

dance steps to shihogiri, but if you do a really good nuki tsuke in

ushiro, I'll give you your bonus points.

In the martial arts

there is live or die. There is no percentage in learning a hundred kata

if you aren't good enough at any of them to beat an opponent. Learn one

thing well and do it with commitment, you might survive to learn another

thing. Do the "advanced" ushiro in front of me with less than 5dan

under your belt and I will look at your left foot. Really look at it. If

your turn and shift isn't rock solid I'm going to be upset because you

didn't have to use that turn. Impress me with solid basics, not esoteric

theory.

I have a youtube channel somewhere and I think I

uploaded a video on this "advanced" turn last night. If you're

interested see if you can find it. There's a link at the top of the page actually.

|

June 28, 2013

|

Teaching

|

Shu Ha Ri

The basic teaching method for kata based martial arts is "keep, break,

leave" which is usually interpreted as memorize the movements, break

them down (understand them) and leave them behind (to go beyond the

kata). This is the typical Confucian "practice first, theory later"

method of learning and it works well for us, although many western

instructors tend to hand out the theory at the

same time as the practical. It really is OK to let beginners simply

follow your example and copy the dance steps until they have the

movements memorized. At that point you can introduce kasso teki and

explain what is happening with targets and swords. Don't think that shu

ha ri is a one-time process, it is more of a spiral as we use the

"leave" phase to understand something more, something deeper in the kata

which then requires more shu and ha. We dip into and out of the kata

repeatedly as we practice over the decades, it would be a shame to

assume that we know it all when we know the first layer.

|

June 26, 2013

|

Teaching

|

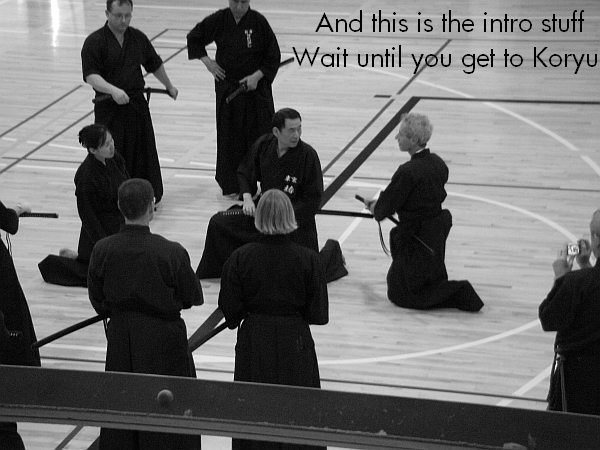

First is not always beginning.

I notice on one of the forums that a student has once again commented

on the zen ken ren iaido as being the beginning set. The set you begin

with could I suppose, be called the beginning set, but it isn't a set

that was designed for beginners.

I recently spent some time in Calgary (before the floods hit, hope folks are going to get a chance to dry out soon) and managed

to write a bit on the "riai of seitei iai" which has a nice ring to it.

Here's an excerpt from what is supposed to be a seidokai resource, but

of course I'll end up putting it out there for everyone else. The ego

knows no bounds.

"The origin of the All Japan Kendo Federation

Iai was as an introduction for kendoka to iaido. This was so kendo

players could learn how to handle a live blade in a situation beyond the

bokuto work of the kendo no kata, itself a set of techniques which

intended to improve the use of the shinai by showing how a blade is

properly used. Being for the benefit of kendo players, much of the

fundamental movement of Seitei Iai agrees with that art. Such things as

the importance of a correct furi kaburi (attacking position), square

hips, and the ability to follow through after a strike are built into

the bones of Seitei Gata iai and they remain there today, stronger

perhaps than ever before.

While the intent in 1968 may have

been to provide a training aide to kendoka, iaido under the kendo

federation has become more than an adjunct to shinai practice and there

are now many kendo federation members who practice only iaido. It should

be remembered always that an introduction is not always introductory.

By that I mean the Zen Ken Ren iai (usually called Seitei Gata Iai or

representative forms of iai) was not a set intended for beginners to the

sword or to be used as an introduction to iaido. Those who developed

the Seitei were senior practitioners of various koryu iaido schools, and

anyone who practiced iai at that time, was similarly a member of a

koryu. Seitei then, was a representative set of kata which demonstrated

the variety of movements and the use of the live blade to kendoka who

were likely quite senior in that art and wished to go deeper into the

meaning of the sword. Seitei was not intended as a set of kata to teach

beginners. Those who wished to learn iaido would have been expected to

join a koryu.

The reality today is that Seitei Gata has become,

for many, their introduction to iaido. Iai clubs under the various

kendo federations worldwide use the Seitei set as their grading

curriculum and so instruction in that set begins early if not

immediately. There are, in fact, many clubs worldwide that practice only

Seitei. The International Kendo Federation claims no authority over any

koryu iai schools, and so when senior instructors are sent officially

to teach they are required to focus on Seitei Gata exclusively. While

many of the senior iaido sensei in the kendo federation may also teach

koryu, this is done on a private basis. All of this has created a

situation where the Zen Ken Ren iai is in reality a school of iaido in

itself, and should be considered as such by its students and

instructors. Over the past several decades the iaido committee has

interpreted, clarified and in some few cases, modified the original

instructions so that the school has become more internally consistent.

What was once almost an accumulation of kata from various old schools

has become an entity in itself."

So there you have it, seitei

is something you start early, but that's your introduction to seitei.

Don't think of it as an introduction to koryu, that's something else

altogether.

|

June 25, 2013

|

Remember

|

John Prough: 1940 - June 20, 2013

John Prough, perhaps the most underappreciated man in North American

Japanese Sword circles died today. I met John by letter in 1987 when I

started the U. Guelph iaido club and was trying to find any and all

iaido students in Canada and the USA. Through his help and encouragement

I started the Iaido Newsletter which was a photocopied 'Zine that

eventually grew into worldwide

distribution, then the Journal of Japanese Sword Arts and finally the

online Iaido Journal at EJMAS.com. The contacts from that magazine

quickly grew into the Guelph Spring Seminar and the CKF iaido section,

the structure under which most iaido students in Canada now practice. It

was through John's introductions a few years later that the CKF jodo

section also came into being, so students of both sections should pause

and recognize one of our most vigorous supporters.

The following is an interview with John conducted in 2004. Take a few moments to read it.

http://ejmas.com/tin/2004tin/tinart_morgan_0404.html

How Will You Be Remembered?

When I think of loss, specifically loss in the budo, the folks I

remember right away are the ones who built. Matsuo Haruna, Peter Yodzis,

Bill Mears, John Prough and many others in this generation, along with

those I know from previous generations, were all promoters, builders of

the arts. Those who have passed from my lifetime who were mean-spirited,

selfish or jealous of their knowledge are much harder for me to

remember, and those from previous generations who were the same aren't

much remembered at all.

Let's be honest, you don't usually get

remembered for being the guy who kept the arts small and exclusive, for

not teaching students, not sharing the arts. For being selfish, not

growing your knowledge, not being open to new blood and new ideas. Or if

you are remembered, it's for those things.

The builders get

the memorials, the bean-counters who figure knowledge is money to be

hoarded and denied or used to buy some sort of sham respect, get to put

their signature on an audit report which may, perhaps, be looked at by

some future historian who is doing research on the other guy.

Think about those you admire in the arts, what is it that you admire? This will tell you something about yourself.

Be a teacher. Haruna sensei was one of the best teachers of iaido I've

ever met, and I've met a few. He was open, loved beginners, and would

fix in a word or two what you had been struggling with for years. More

than this, he welcomed non-Japanese students and more than once put his

own career on the line for our young organization.

Be a

facilitator. Peter Yodzis started an Aikido club at the University of

Guelph in 1980 and brought Bruce Stiles from Toronto to teach every

weekend. The club is still going strong 30 years later with one of the

original students now instructing.

Be a populizer. Bill Mears

was fond of saying he didn't advertise and made it very hard to find his

club. He said this a lot on various forums and email lists on the newly

minted WWW. It wasn't that hard to find him and iaido is still growing

in the Niagara Peninsula under his students.

Be a student.

John Prough had the chance to set himself up as a big sensei in the New

York area, he had the early training, and was in on the "ground floor"

of the koryu craze (if there ever was one). Instead he repeatedly

brought in teachers and rebooted the arts.

Are you in it for yourself or are you willing to set your ego aside so the arts themselves can grow?

Small-minded or big-hearted? The answer will determine how you are remembered.

|

June 24, 2013

|

Grading

|

Gradings Wrapup 2013

Well the summer grading season is over for me this year, with CKF

gradings in iaido and jodo in the east (Guelph Spring Seminar) and jodo

in the west (Vancouver).

There was the usual fuss and bother

that you get with such things, but on the whole the gradings I attended

went as well as they ever have. Here are some things currently on my

mind which I've come to believe over the years, either through judges seminars or just paying attention so I'll share them with you should you wish to keep reading.

It's a hobby folks:

Judges and challengers both have to understand this. There is no money

involved for the students, you won't make more salary if you pass, you

lose nothing (except some hefty grading and travel expences, granted) if

you fail, don't sweat this stuff so much. Judges may get an honorarium

but mine go into the CIJF fund unless I'm out of pocket for my own

travel expenses. Judges don't get any benefit for failing or passing

people. They just get to watch and opine. Not the ego boost you might

think by the way.

Students want clear rules:

Not an

unreasonable thing, but what does that mean? I know that it does NOT

mean last minute changes. Any variation over what was announced, or what

was past practice should be applied only after everyone has a chance to

hear about the new deal. On any panel I've been regularly associated

with, any changes have been applied carefully, and at least a year

later. For instance, this year the start and finish line was clarified

further and we could have failed 100% of the challengers in the Eastern

iaido grading. Not one of them did it the way they will be doing it next

year, but they did it the way they were taught. So they passed that

bit.

Fair enough, but what about putting a time limit on the

gradings just before you start? Time limits are a pet peeve for me, they

are great in tournament where you have to move along, and maybe in

gradings of several hundred challengers, but for 40? They aren't needed.

They make for lazy judging (it's an auto-fail like doing the wrong kata

or the kata out of order, so you don't have to look at anything else)

and for the lower grades it should never be done because the easiest way

to prevent an automatic fail is to rush like hell through the kata. Any

teachers out there think it's a good idea for beginners to rush their

techniques? So why force them to do it with a grading time limit?

The biggest problem though, is the "regional variation". There are

things that are mandatory (read the books) and things that are allowed

(theoretically, anything not in the book, practically, anything that

doesn't make the judges' teeth hurt). If local panels are not

experienced or trained enough to understand the difference, there are

problems with challengers from outside that local area. This year the

west coast jodo head came to Guelph on his own dime to make sure he knew

what the east coast jodo folks were being taught. I also made sure that

I attended a full day seminar with the west coast folks to understand

what they were being taught. The book was respected on both sides but

other things have a very distinct flavour. I like that, the world is

full of fast food restaurants, who needs another generic burger?

Judging seminars are the answer, but when your country covers a quarter

of the way around the earth, someone has to be willing to spend a lot

to get the local panels on the same page. Not always easy without an

independent source of funds.

You gotta trust:

It's

all voluntary folks, I don't know if it's the requirement for drug

testing rules on the kendo side of things, but there seems to be a lot

of concern with injuries and disabilities starting to show up. "In

Japan" they require a doctor's note if they can't do seiza. Should we

do that here? I vote no to that. A note from a doctor is an extra

expense for the challengers, and who reading this figures they can't

talk their doctor into a note that says you are not allowed to bend your

knee to the absolute maximum it will go and then drop your entire body

weight onto it? (Personally, if we ever permit doctor's notes I'll have

one in a heartbeat and never try to do seiza again.) Seiza would be

banned by labour law if employers ever tried to make their workers use

it. I say trust the people you are willing to stand with in a small room

while swinging sharp metal around. Trust them not to cheat, if they say

they can't do seiza, they can't.

Judge and be Judged:

The judges on the panel are being judged just as much as they are

judging. How the students are treated will reflect what the students

feel about the organization since the gradings are pretty much their

only contact with that organization. I can't tell you the contempt...

not quite the right word... lack of respect?... I feel looking at a

grading panel covered with water bottles, judges lounging around in

various arms folded or heads on hands poses with their eyes half shut.

Not at my table, not if I'm in charge. The challengers work hard to get

to the grading so that they can show you their best. You have to show

them the best judging you can. No water bottles, no elbows on tables,

and put a curtain on the table so you can cross your legs once in a

while to prevent cramps. Contempt breeds contempt, you want respect as a

judge, respect your challengers, respect the position of judge.

What is the point of grading?

Challengers and judges need to ask this of themselves. There are

several ways to approach grading, for challengers it can be an attempt

to get a rank, a donation to the organization in the form of the grading

fees, or maybe a thank you to your sensei through showing him that you

have learned something. Most healthy though is to treat a grading as a

chance to review the basics and clean up your act.

Judges can

approach gradings in two broad ways, juniors tend to go in looking for

mistakes, checking for the details (just as beginners to the art itself

have to focus on the physical techniques). Senior judges tend to be more

"easy" than junior panels because they look for reasons to pass the

students. The function of a grading is not to see if students fall apart

and make mistakes under pressure, it's to assess whether or not they

are at the level they are challenging, so a look at the overall

performance is best. Now the level of a shodan is nowhere near the level

of an 8dan, and if an upper level challenger shows up on the day of the

grading looking nervous they may as well go home again. 6dan training

is not 3dan training, and the grading requirements reflect this.

Fundamentally, a grading ought to be an assessment of your level of

training. Are you at 5dan level or not? Everyone should be at the

grading with this in mind, students should not be upset if the judges

say they are not, after all your sensei said you were when he signed

your form and who's more important? Just get on with it and come back

next time. Judges had better not have anything other in mind than the

requirements of that level. If we look for things beyond what the rest

of the world requires, we are not being clever or strict, we are simply

being unfair. The whole point of standards (requirements for rank) is

that they are standard. The only reason to require more from your 3dans

is to try and win the next 3dan tournament and that's a lousy reason to

skew the system.

So why grade at all?

Good question

and all I can say is that having your appropriate rank solves some

problems. If you are ranked too lowly or too highly the powers that be

don't know what to do with you. There are teachings that are aimed at

certain knowledge bases, so you split up into ranks. If you are ranked

too low or too high you're wasting your time.

One of our

seniors in iai never graded for many years. One day he was in Japan at a

big seminar and he ended up in the non-kyu group. The sensei of the

group came over and said "the 6dans are over there" but he said "I have

no rank". This created a problem, he could not join the 6dans and he was

an embarassment to the beginners and their teacher. Better to have

assigned him a fake rank or to have simply told him to test and be done

with it.

How come you aren't sorted into knowledge level

instead of rank? How come you can't simply join the group that is doing

stuff at your level? ... Seriously? You're now the judge of your own

rank? ... You want every seminar to start with an assessment by the

teachers of your ability? That's a grading for every damned seminar!

You grade so that we can have fewer gradings, that's why you grade.

|

June 18, 2013

|

Teaching

|

The Teaching Bomb

I'm writing a book for my students at the moment and it includes quite a

lot of advice on how to teach. Thinking about my own budo education, I

wonder just how much I really need to say. In my case some of my biggest

advances have come through a single "teaching bomb" dropped into a

class by sensei.

About twenty years ago Haruna sensei took a few moments during a break and showed

me two ways to swing the sword, one was the way I was swinging it, the

other was the way he swung it. Up to that point I wasn't aware that

there was a difference at all, but that single episode (and he made me

swing until I managed one his way) set off a decades long journey that

I'm still travelling.

Jump forward maybe ten years and Ohmi

sensei (my shisho, main instructor) commented to a class that they were

practicing a partner kata much too closely, "maai" he shouted, "you are

inside the maai and already dead before you even start the kata".

Although not aimed directly at me, I listen to all his instruction and

this statement exploded in my head like a bomb and I have been happily

searching for the meaning of maai ever since. Looking at the sword, at

the distance from me to my partner (or my kasso teki if I'm doing iai)

at posture, at my natural stride length, and at the energy I can summon

from day to day has changed the way I practice.

This bomb has

combined with all the previous bombs, including one from Ide sensei

regarding what I call the "instant of furi kaburi" the moment you can

begin attacking the opponent, the "decisive moment" to use a photography

term from Henri Cartier-Bresson. All these more or less throwaway

comments which have hit me at just the right time to trigger cascades of

understanding make me wonder just how much special lesson planning

anyone needs to teach. After all, they were simply corrections that are

given as a matter of routine to all students. They weren't anything

special, they weren't secret knowledge passed along in a whisper in the

corner of the dojo, they were just everyday corrections that seemed to

explode.

This is what's meant by "when the student is ready,

the teacher will appear". It's not so much meeting a teacher as priming

an explosion and having someone toss a match at you. Could be anyone,

but yes, it's often a special sort of instructor who can see that pile

of gunpowder just waiting for the spark.

|

June 9, 2013

|

Psychology

|

Budo Self-Examination

A couple of posts ago someone commented "Many arts will feed the

misguided student's ego through the art's inherent superiority complex".

Nothing is easier than believing your art is the best around,

or your teacher is the best. To a very large degree this is a good

thing, you can't fight well without believing that your skills are

superior, there is no basic training program

in any military anywhere that teaches its soldiers that their skills

are at best equal to the enemy and their equipment average.

But the budo were never about creating cannon fodder, the martial arts

are not basic training, and having enough blind faith in the system to

plunge into the breach with a lot of other soldiers is not the goal of

this training.

What is needed is enough faith to keep showing

up for training, and a great big dose of self-examination. Those in

duels, those who lead and those who wish to improve as human beings need

to watch themselves constantly to guard against false pride and the

stupid acts that follow. Here are a couple of hints.

The

Monitor: This is a small part of your mind that you detach and place

just above, behind and to one side of your head. I'm right handed so

it's over my right shoulder. My family was superstitious so the spilled

salt goes over the left shoulder. The monitor watches, that's it. Sober

or drunk, calm or angry the monitor watches what you are doing and what

you are thinking and nothing else. What you do with the information is

up to you but the benefit is simply the audience effect. Think of how

you act with and without an audience.

Next is the Analyst: You

can use the information from the monitor, or use thought experiments to

examine what you would do in this or that situation. The analyist's job

is to figure out why. Why did you say that? What were you trying to get

done? You must be ruthless, it does more good to identify bad intent

than good, beware of sainthood.

The Planner: No battle plan

survives contact with the enemy, and no good intent either, but planning

how to live your life well is the essential first step to improving.

Planning how to get the most out of your next class (have I got my belt

and my bokuto in the bag?) is the first step toward a fruitful class.

Yes mushin is a good thing, yes you have no time to think about your

next block and counterattack during the fight, but you're not fighting

now are you?

I am constantly stunned by how little foresight

people have. Look around you as you drive down the street, I watched a

car in front of me yesterday, left him room to change lanes after he

passed me because there was a big truck, unmissable, stopped in his

lane. I watched this guy see the truck when the car in front of him

moved over, watched him panic and swerve at the last minute, no blinker,

into my lane as he prayed to his gods that I wouldn't rear end him. A

tiny bit of foresight would have saved him an anxiety attack. Luckily I

drive for everyone else on the road as well as for myself.

Monitor, analyse and plan your next six days and see how that goes.

|

May 15, 2013

|

Seminars

|

Seminar Advice

The 2013 Guelph Spring Iaido and Jodo Seminar is about to start. Every

Victoria Day weekend and for the last 22 or so years. I look forward to

the same old problems and complaints from those who attend and those who

teach.

The seminar starts on Friday evening and I look

forward with somewhat negative eagerness to kicking out all the juniors

who will be expecting to watch the senior

class. It is somewhat mysterious what folks think they will see, it's

just the dojo leaders getting their asses kicked by the Japanese sensei

and a passing along of any new interpretations of the performance of

seitei gata jodo and iaido. In other words the same thing that happens

for the next three days.

I get that folks are eager to be in

the class, after all it is "dojo leaders" so I suppose you could

convince yourself that being there means you "made it" but I hate to

disappoint, it's not by rank or invitation yet, it's a self-selecting

group. Now this year I've tightened things up due to high numbers last

year so I will be booting non-pre-registered folks out of the room but

all that means is that those who are "in" managed to pre-register.

Every year I get told to get a bigger room but that's not going to

happen, we want this small and quiet so the seniors can pay attention.

On Saturday morning I look forward to people turning up at 9am (the

seminar start time) to register. Registration happens before the start

of the seminar, not when everyone is to be on the floor for the opening

talks, but hey, if you pay you get to come whenever right?

Speaking of paying, I don't mind dickering, I don't mind haggling or

folks trying to combine one rebate with another until I'm paying for you

to attend but do not, repeat, do not dicker and argue with Dave at the

front door. He will just boot you to me and I will be too busy to

indulge in the game. All dickering and haggling should be done before

the end of the week OK. By the way, the fees cover the expenses, so be

happy about paying a couple of hundred for 3 days solid training instead

of a couple thousand to fly to Japan aand train a couple of hours a day

if you're lucky. We use the sensei quite cruelly as I've been informed

in the past, they go home exhausted.

Lining up: The most

difficult part of any seminar is lining up in a zigzag pattern at the

start of the day so please folks, practice this at home, get the dojo to

make three lines of students, the first line stands far enough apart

not to hurt each other, then the second line stands in the spaces

between (far enough back to avoid hitting the first line) and the third

line goes in the spaces of the second, lined up with the first line, and

far enough back not to hit the second line. And So On.

If we

have to go up and down the lines fixing you, do not, DO NOT resist me

sending you where you need to go. I don't care that you want to stand

right in front of the sensei and that you figure everyone else in the

room should arrange themselves around you. I'm big and I'll be angry by

then, I'll send you to the back line. I will, I swear I will. Fifteen

minutes of lining up is excessive, we should not need that long.

Oh, and the seniors will be on your right hand side, find the last

person on your row to the right and line up with them, not wherever you

feel like it. If the seniors get it screwed up we'll have a chat with

them I promise you. (Actually it's the seniors who have the hardest time

with this stuff, the juniors pay attention and do what they're asked to

do).

There will be a class timetable at the front desk, it

rarely survives contact with the sensei so don't come complaining to me

that you have arranged your day around a class that just shifted by two

hours. I'll say I'm sorry, but I don't set the schedule (and I'm not

telling who does because they'll just boot you back to me anyway).

Pay attention, go where you're told and relax Saturday evening at the

auction where we'll feed you roast chicken (a tradition is a tradition)

and by the end of the evening we'll all be settled down to the routine

so we can start again the next day by spending fifteen minutes lining up

in a zigzag yes?

I joke, 22 years along we've got this down right?

|

May 13, 2013

|

Health

|

Murphy's Law of Martial Arts Injury

It never fails, I work for months in the gym to put knees and shoulders

together in preparation for the Spring Seminar (I pick the sensei up

from the airport on Thursday) and while working in the shop I wrench my

shoulder.

I was sanding some paddles for the SDKsupplies.com

table when I dropped my palm onto the 24 grit sandpaper. Needless to say

I twitched the arm upward and in the

process managed to re-injure my shoulder. Of course there's not a mark

on my hand. This morning I can barely turn the steering wheel on the

van. I suspect I've got about two attachments of five left on my rotator

cuff. At least the original injury was a more interesting story, being a

teaching mistake in an Aikido class, when I couldn't drop low enough

due to a knee injury and so went straight into my uke's power with the

rotator cuff.

All I can say is that those paddles better sell.

|

May 13, 2013

|

Learning

|

More on What To Study

I have no inspiration this morning as Lauren is having her breakfast

and I'm being the usual guilt-driven workaholic, writing while drinking

my coffee. It gets worse in the runup to the May seminar http://seidokai.ca/iai.seminar.html

as I obsess about all the setup that still needs to be done. A bit over

40 people signed up so far, almost got the air tickets paid off, double the numbers and I may be able to pay for the hotel rooms!

Here's a bit from a past forum post on what you should study. I sense a

definite trend in what students want to know and what their seniors

tell them to do, often not the same thing. T'was always the way with the

young and old yes?

What to study? I want to study a koryu, a

nice rare one, what do you suggest? And I don't want to learn it at a

seminar because that's just seminar learning.

Do what's in your

back yard! Go do Kendo or Judo. People eventually "get a life" and so

stop doing the long distance commute to learn a martial art. Especially

when they find out what "koryu" is.

Now please, if

someone wants to move to learn Niten Ichiryu, and are dead keen to learn

it than don't you think it would be a really really really good idea to

meet the headmaster of the style in a place where you could show him

just how serious you are? Like when he's in North America for a week? No

letters of introduction needed, no need to fly to Japan, just drive to

Guelph (a couple hours north of Buffalo NY) and step on the mat. No need

to even have your own bokuto, we loan them out!

(Incidentally, we DO get people from all over Europe and North America

at the seminars. Just damned few of them in total and I think it's

because koryu is not in demand any more than it's ever been, it's just

in style as the next "cool secret martial art").

It has

been suggested that people don't attend seminars because they don't know

if they'll get the instruction when they go back home. This makes no

sense at all to me, you train when and where you can. If I didn't invite

sensei to Guelph, I'd be flying to Japan and Europe to train. If

"future training" were a factor then potential students would email me

and ask if they can learn this stuff elsewhere than the seminars. They

don't. They want to learn a secret Japanese martial art that's really

really exclusive... and that's just around the corner from their house.

Surely you know the story, a little old Japanese fellow sees you walking

by one day and calls you into his back yard to pass on the wisdom of

the ages through some obscure branch of a martial art nobody's ever

heard of. That's what folks want, not to hear "make an effort, come to

me and I'll teach you".

'No', you say, 'there's a demand for koryu, I feel it in my bones'.

I figure there's a demand for koryu that's just around the corner where

the local karate club is. There's no real demand for koryu per se. If

there were we'd have folks coming to the seminars to meet the people who

could teach them.

It's as simple as that.

Major seminars have been happening in Guelph since 1991. They aren't a

secret or hard to find out about. They're even pretty well known in

Japan since they're written up in the martial arts magazines each year.

Google Iaido, google Niten Ichiryu, there we are.

I

started The Iaido Newsletter in 1987 before there was a WWW, back when

we hunted mastadon and mailed stuff with stamps, just to connect all the

North American folks who had an interest in iaido so we could get

enough people together to invite a sensei from Japan for a seminar. Now

you type 5 letters into google and hit return.

Not hard to find, just not around the corner.

But, someone said: "You're correct in asserting that the demands of

koryu training can dissuade some from joining, or the teacher sees

deficiencies or potential problems and doesn't accept the candidate."

I absolutely do not assert that the demands of koryu training prevent

students from joining, or that teachers will not accept students. In no

way do I say that. I said that most teachers simply demand that you show

up on the floor. I know of damned few martial arts teachers of koryu or

any other art that demand students do anything special beyond showing

up to join.

Some do, and more power to them since they

attract the folks that want that sort of thing... and some folks do want

that sort of thing.

I maintain, as always, that my way

is the absolute most rigid "test" of a student of all. I get people

asking to train with me (who assure me that they want to do my martial

art for the rest of their lives), who wonder what sort of introduction

letter or special training or money they have to give to me to be

allowed the rare and amazing honour of training with me. The task I set

them is to "show up on the floor".

They never ever do. Not once have I had someone who's expecting a "test" pass my test. Zero percent pass rate.

Pretty tough test.

Incidentally, we're talking about people who say they will "move

anywhere to study koryu" not about the vast majority of people who want

to find Mr. Miyagi the next block over, and I reiterate, get your life

in order and then see if there's some koryu around. Do NOT move

somewhere simply because you figure you want to learn some martial art

you've never actually tried.

DO go to a seminar that

offers koryu and see if it's what you want to chase for the rest of your

life. They exist, you don't need to jump through hoops, you just need

to show up.

There are more seminars on the Olde Japanese

martial arts than ever in North America, take a week off and see if you

want to spend thousands of dollars and dozens of years chasing the

rabbit.

|

April 29, 2013

|

Balance

|

Martial Arts

and Career

Driving the wife to work I happened to hear on the radio that having a

dog is a good career move. The daily walks give your brain a chance to

rest, and the daily timing of feeding and walking gives structure to

the day. So if you are self employed, get a dog and your business will

improve.

I figured that out while attending University, where I used my martial

arts classes to structure my week. All

my classes and all my daytime free time (devoted to runnng, lifting

weights or practicing budo on my own) were arranged around those

evening practices. I never had less than 5 sessions of budo a week, and

often twice that.

It worked out well, the practices themselves meant I couldn't be

thinking about the current girlfriend, exams, or essays and getting out

of the apartment to go to class was enough to get other things going.

Most of the effort is expended getting off the couch, the rest is just

momentum. Strangely enough, filling my week with things to do gave me

more time to get my schoolwork done. With only a couple hours to work,

I made the best of it and worked, rather than procrastinated.

Ever wonder why office buildings still exist in this era of home

computing? The act of getting from one place to another has value to

the working process.

Over the years I've had folks say "when I'm working I don't have time

for martial arts and when I'm unemployed I can't afford martial arts".

Fair enough, but my classes don't cost a penny, just show up in class,

and perhaps a break of a couple hours three times a week might do some

good to the old brain cells. Consultants make more money the faster

they work, it's only pieceworkers who make more the longer they work.

Got a kid heading to College? Consider telling them to take up some

activity that wastes their time on a regular basis.

|

April 19, 2013

|

Learning

|

Just how Senior

Does Your Teacher Need to Be II

Thomas Groendal wrote: "Another

purely practical concern: if the hachidan hanshi is a one in a thousand

or one in ten thousand genius, but only has time to really teach a few

hundred students at best from beginner to the end of their potential,

the math is not good. The art will die.

If his intermediate level students are out there cycling through

another thousand or ten thousand students though, someone brilliant

will answer the call. That hachidan hanshi will know her when he sees

her."

An excellent point. I have seen more than a few clubs in this area with

top-rank-loaded students and very few beginners during times of

decreasing enrollment. Lots of rank that could be out teaching but they

stay "at home" because, so they say, they haven't learned enough to go

teach. Over the years some of the more honest have confided to me that

it's more usually laziness than insecurity, it's just easier to stay

and practice than go out and teach.

Indeed it is. It's also a lot more fun for a bunch of high ranks to

play with each other at their high level rather than teach beginners.

Let's face it, beginners are a drag. One of the super-rank clubs I was

involved with practiced Aikido and I can tell you that as a young, fit

student with enough years of practice to protect myself, it was a blast

to practice there. As soon as the students found out you weren't going

to break when you fell it was spin city for the entire class. You could

almost hear the thoughts of "fresh meat!"

It was of course small wonder that there were few beginners and those

that wandered in didn't last long. This was not a unique situation,

most of the clubs filled with high ranks taught only by the headmaster

tend to chase out beginners. Now, there are some super-rank clubs who

make provision for beginners and these often give the beginner classes

to these same middle ranks that Thomas suggests could be out teaching

their own clubs. In fact there are clubs within clubs in these dojo,

with beginners picking their instructors if they can, and avoiding

others.

Needless to say this usually happens in a big city with a very highly

respected and ranked instructor in a private club. It doesn't

happen so much in small towns where the teenaged prodigy leaves for a

career, or University settings where you have an inherently transient

pool of students. I know that the lament of every sensei here in Guelph

is just the same as the parental lament heard just before we get the

students walking in the door... "they just start to get interesting and

they leave!" Thank goodness for grad school and those students who stay

around more than four years.

Back to the super-rank clubs and what happens to them eventually.

Firstly, no matter how many people start in that magical cohort that

turns into the upper-rank stay at homes, the numbers in the club

eventually start to shrink. No matter how good sensei is in these

clubs, eventually the students catch up, at least physically if not

altogether. Sometimes sensei takes this well, sometimes not. Sometimes

sensei adapts and becomes softer and/or sneakier and sometimes he just

becomes grumpy and hard to get along with. Regardless, the seniors

eventually start to leave, and this time the opening up of new dojo may

be used as an excuse not to practice "back home" much.

Once I noted that a head sensei chose to leave the club at the height

of its power and skill. The students were starting to challenge sensei

and rather than booting them all out, he left. This interesting

experiment didn't result in anything different really, a new top dog

emerged and eventually the rest of the upper ranks drifted off to start

their own clubs.

The problem with this model is that by the time the super-rank club

fissions off its instructors, they are past their evangelical fever.

They are usually looking for some place to practice in peace rather

than looking to spread the good word. The original club isn't much

better off, it's not easy to remember how to recruit new beginners

after 20 years of ignoring them. There is a window of youth and

experience that makes a great beginning instructor, go through either

of those and you lose a lot of potential new students.

So how does a head sensei avoid the super-rank club syndrome? Some have

no interest in avoiding it at all, they like the fact that they've got

all this talent under them. They may encourage students to stay by

hinting that they haven't the skills or experience to go teach.

Fortunately this is rarely the case in my experience, most super-rank

clubs are a function of their situation as I mentioned above. Big

cities mean expensive practice space and lots of students at those

spaces which do exist. A large initial pool of students will produce

lots of rank in very short order and it's only gradually, and if sensei

isn't paying attention, that the rank eventually starts chasing out the

beginners. By the time anyone notices, it's a super-rank club.

It takes effort to avoid this. First step may be to set up beginner

classes within the club and keep that cohort together under one or two

of the lower ranking people. Eventually the ranked survivors get

transferred to the senior class and the senior sensei. If a chance does

comes up to start a new club in a nice location, the head sensei ought

to have a senior student in mind and push him or her out the door with

many promises of lots of help with the new club and the chance to come

on back for special high level practices so that the new teacher can

keep learning.

I'm sure there are lots of other ways to deal with the super-rank dojo,

but most of them will come down to sensei paying attention to what's

going on around him. Sort of like everything else in the arts, it's all

about noticing the tiger in the bushes.

|

April 19, 2013

|

Learning

|

Just How

Senior Does Your Teacher Need to Be

This is a perpetual question for students and the usual answer is "your

teacher should be as senior as you can find".

But over the years I have come to wonder about this. Do you really need

to study with a hanshi when you are a beginner in iai? Is it a good

idea?

There is no doubt that a hanshi "knows things" but in any physical art

there's a large amount of "shows

things" at the beginning. As I am well aware, even a 50 something 7dan

(a position where you are, supposedly, as strong and technically able

as you will ever be) can, as in my case, be losing the edge, or at

least the knees, to be able to demonstrate really top-level iaido. I

can't imagine the frustration of some of the hanshi who have come to

the end of their joints, who know exactly what's needed to demonstrate

a point, but can't do it.

Sure they can ask some of those 50 year old nanadans to demonstrate,

but watch carefully and you'll see the pain behind the eyes when their

point doesn't get made.

A few private words to the nanadan and whole worlds can open up for

them, but what does this hanshi offer to a first kyu? Perhaps not as

much as you might think.

The first kyu.... never mind that.... the iaido and jodo students all

the way to fifth dan are learning how to dance, how to perform

technically perfect kata. This involves the correct footwork, the

correct movement of the sword, the correct timing, pressure, strength,

posture... things that can take decades to learn. For all of that the

best teacher will be someone who can demonstrate all those things in

the correct sequence for the students to take them on board. It doesn't

require a hanshi and for my money, one should not be provided. The best

teacher for a strong young man is a stronger young man. Someone who is

ahead, but not so far ahead as to be past the things needed to be

learned by a beginner.

Three years ago I stood in front of a hanshi and he showed a grip on

the sword that moved my hands a centimeter. The 6 and 7dan people in

that class were delighted and we are still talking about it. I of

course showed all my students and one or two yondan sort of got it.

Nobody below that level of experience even came close to getting

excited like I did, probably because they didn't feel what that grip

did to the little toes or the shape of the sword as it dropped. Their

skill level wasn't high enough for the correction to make any

difference.

So what use would it have been for a yondan to sit in on that class?

None at all, they would have looked and said "big deal, I know how to

hold the sword, how to sit, how to breath, what's this old man doing?"

(Or even worse, speak up and ask him to teach them some sort of lost or

secret kata they read about on the internet).

Be careful what you are trying to learn and from whom, the best sensei

is one who can take you to the next step, not one who is so far down

the road he never saw the pothole you are about to drop into.

Never saw it because it wasn't there when he went past.

|

April 18, 2013

|

Teaching

|

How Long to be

a Big Shot

Let's say we want to be a big wheel in your organization. No idea why

you'd want to be, but here's the times in the Kendo federation. You can

put people forward for grading at 5dan in the CKF, you can sit on a

panel to any grade up to 7dan at 7dan. There are two grading streams,

the dan and the shogo which are renshi, kyoshi and hanshi. For Canada

we don't really use shogo for anything

so think of them as 6.5, 7.5 and 8.5 dan. They aren't technical grades,

so that's really not accurate but like I said, they don't have much of

a function in the CKF. In Japan the shogo have much more meaning and a

hanshi is in fact a Big Shot.

So for timing, it's about a year to shodan, 1 to nidan, 2 to sandan, 3

to yondan and 4 to godan so 11 years minimum to 5dan. Another 5 to

rokudan and 6 to nanadan for 22 years all at max speed and no

failures... ridiculous if you think about it, who needs 20 years to get

good enough to teach something? 11 to godan seems plenty to me. How

long does it take to become a surgeon and muck about in someone's

innerds?

Hanshi... hmm, another 10 years to 8dan is 33 years... then a few more

before you can challenge hanshi. That's it though, nothing more above

that at the moment in the federation.

But are you ever a big shot here in the West? There's 7 and 8dan sword

instructors in the west, why are all these young-uns wanting to go to

Japan? Nice place I'm sure, but if the goal is training it's a lot more

practical to do it where you live... maybe move 300 miles instead of

3000? Just thinking out loud here... I mean of course you have to go to

Japan to become a samurai, either that or find some funky old gardener

on the back street of your local town who teaches you in 3 months.

20 years... and how many failed relationships due to the obsession?

Ridiculous.

For all those who are currently teaching a class somewhere in Canada

with a 3 or 4 dan because you're the only teacher available... good on

you. With 4 to 7 years of training (around the time it takes to get,

say, an MSc in University) I'd say you have a good chance of being able

to teach something useful to your students.

As far as I'm concerned, you're already a big shot.

|

April 16, 2013

|

Balance

|

Busy Busy

My daughter was born 19 years ago, just around the time of our December

Grading weekend. I was there at her birth and it sort of bothered me

that I was letting the organization down, but that's OK I have made

every grading since. In the process I missed pretty much every birthday

party for my daughter along the way, but you know, priorities, the

organization is important, budo is important.

Part of martial arts is personal responsibility and putting the welfare

of the group ahead of your own selfish wants. It's the warrior way.

Right?

So now I'm looking at ways to convince her that commuting to university

from home is a good idea rather than moving away. I hardly know this

kid, and it's only yesterday that she was born it seems. There are big

gaps in my experience of both her and her brother and I'm wondering why

that is.

I can't begin to tell you how many times over the last 19 years I have

had a student say that they can't make this or that budo event due to

some family commitment. What about their commitment to budo? I mean I

make all the events, and most of these are really important, visiting

instructors, special classes that sort of thing. It seems like we just

get a promising teenager started on the arts and then they get married

and get a job and poof, they disappear.

Me, I always looked for jobs that let me take time off for seminars, I

had a wife that didn't mind that I was gone, I had kids that said they

understood when I had to go away for the weekends.

Now it seems that they are busy when I get the occasional weekend and

want to do something family-oriented. They've got their friends and

just can't be bothered to be away from them long enough to go on a

drive or to the cottage!

Folks, listen to one of the old men for a change (it is never popular

but I always benefitted by listening to them when I did), figure out

what's important. Your kids are with you for about twelve minutes so

put your budo on slow-cook for the time they are growing up, put your

golf, your gambling, your boozing and your banking on hold and enjoy

these little people while you can, they grow up in a blink but they

remember everything that happens during that blink for the rest of

their lives. Do you remember growing up? Remember how long that took?

You as a kid were on one time scale, you as a parent are on another,

and they aren't a match. At four it takes your entire lifetime to get

to eight. At thirty it takes no time at all. Don't judge the time you

have with your kids by what you remember of kid-time, you'll miss way

too much.

I'm sitting with my daughter right now, writing this of course, rather

than talking to her, but we do notice the old men in the coffee bar.

They've got time for each other now, too bad they were too busy for

their kids, too bad they had a job and maybe a hobby and they always

had "next week" to do something with the family. Next week isn't the

same to my daughter now as it was twelve years ago. Her time-scale is

getting closer to mine and she's learned well, she puts things off like

a pro.

Do you ever wonder why Gramps doesn't mind babysitting the kids? Wonder

why they get along so well?

If you don't make it to the next grading because your kids are having a

party, I promise won't mind.

|

April 15, 2013

|

Learning

|

Where Can I

Find a College With Koryu to Attend?

With all my heart I'd recommend that you pick your college for what's

most suitable for you, for what's going to educate you best for what

you want to do with the rest of your life.

Then look around and see if you can find a koryu nearby.

Koryu isn't secret, it doesn't take sitting outside the door in the

rain for days, there aren't blood oaths

and secret handshakes and you don't need an introduction letter. Some

schools may be all those things, and if you're the type that likes to

do something "exclusive" by all means go for it but "Koryu" isn't some

monolithic cultural-appreciation club with rules laid down by some

conclave of Daimyo in the 1540s.

The vast majority of people in the west who are teaching koryu (and

there's a lot of them) require that you get your butt onto the floor to

practice and not much else.

But "Koryu" is as much a fad as anything else that's come along in the

last couple decades, with the possible exception that it's a fad

without numbers.

Folks love to talk about it, and dream of moving away to learn it but

they rarely actually turn up on the floor when they get the chance to

practice.

For instance, we had the Guelph School of Japanese Sword Arts going for

over 10 years here, and we rarely got more than 30 people during the

school. That's with soke/fuku soke, hachidan, and menkyo kaiden

instructors from several different koryu coming to hang out and chat

with each other. They were never bothered by hoards of students

desparate to learn koryu.

Frankly, the school continued as long as it did because the instructors

liked to get together and chat with each other, not because there's a

demand for koryu instruction in the West. There isn't.

Want to learn Niten Ichiryu? We had Imai soke and Iwami soke as well as

Colin Watkin (Hyaku) sensei here annually for 4 years. We got about 40

people total. You'd think with all this desperation to learn koryu,

folks would spend a couple hundred Canadian plus the gas to drive to

Guelph to learn some.

Nah, life gets in the way, easier to dream about one day going to Japan

to learn on a mountain than to take a week off and sweat blood with the

top guy.

Koryu isn't a lifestyle and you can't make a living at it, even in

Japan. Find a good college and attend, if you've got some extra time

during your studies, look around for a koryu school. If you don't find

one go practice kendo or judo. You'll get as much or more out of either

of those as you would from any of the koryu, despite fantasies of

secret teachings to the contrary.

And if you're wanting to be a full time martial artist, I strongly

suggest you get hooked up with a good commercial karate organization

that has a solid business plan and put your time in. Concentrate on

learning how to teach kids!

Don't make life decisions around learning a koryu, especially if you've

never had the chance to practice one. Imagine finding an instructor on

the net, moving to the town and registering at a college then finding

out the guy's a know-nothing jerk and the college is at best fourth

rate...

The one thing I've noticed over the years is that before folks know

anything about a koryu they're dead keen to learn it and convinced it's

exactly what they want to do with the rest of their lives.

Unfortunately, the more certain they are the faster they quit when they

find out what it's really all about.

The ones who stay are the ones who wander in and say "whatcha doing".

They live close, they don't have any pre-conceived ideas about what's

happening (so aren't disillusioned that there's no "secret learning").

Did I mention that they live close?

|

April 12, 2013

|

Teaching

|

Iaido and

Disability

I'm not sure why this topic keeps coming up but in the run-up to the

summer gradings I am once again being asked by students whether or not

it's worth them grading or even continuing their study of iaido due to

bad knees, nerve damage or other disability.

We went over all this 20 years ago, but here it is again so here is my

take on the topic.

I'll teach anyone who is in front of me

because I don't think iaido is a matter of copying a book or copying

what I was taught. Iaido is the use of the sword in a way that is

appropriate to the situation and to the person holding the sword.

So having stated my bias, here are my arguments.

If we were creating fighting men, bad knees would be a problem. Bad

knees in the current military are indeed a problem, as are bad backs

and other damage caused by humping loads that are too big over broken

ground. The infantry is being asked to carry everything it needs and to

do it with body armour on. If we were trying to turn out warriors that

had to fight from seiza then we, like the military, should indeed

discard our people when they can no longer do the job. But we're not.

Iaido is not practiced as a method of fighting in defence of the

country, never was.

Iaido from seiza was done because people sat in seiza. There's nothing

magical about the postion, there's just a bunch of kata that start from

there, so we practice from there. What happened the last time the

Japanese sword was used in war? Nakayama Hakudo and Kono Hyakuren took

the seiza and tate hiza techniques of iai and stood them up to create

the iai that was taught at the army and navy officer schools. They

taught standing iai because the modern Japanese army officer wasn't

going to be sitting around in seiza or tate hiza with their gunto

strapped on.

How about tradition? It's traditional for iaido to be done from seiza!

Well it has been since Omori Rokurozaemon invented the techniques and

they were adopted into the school, but seiza wasn't there before that

time. The Omori ryu (seiza) showed up when people started sitting in

seiza a lot. Now we sit on chairs, and to my mind, it's about time a

chair set was developed (not my job). Seiza is traditional but not

necessary, it's useful but not indispensible, you can learn all the

lessons of seiza by using tate hiza or standing, it may take a bit

longer but again, we're not training a military, we've got time. We can

stand up all the seiza techniques, all the tate hiza techniques because

most of them are already there in the standing set, and for what few

are not there, we have good hints.

Tradition is respected exactly as much as the teachers say it is

respected. I'm all for tradition, I figure we should follow it in the

absence of understanding because we need to trust our teachers -

teachers, but let's use common sense, if someone can't sit in seiza,

they can't sit in seiza. It's a choice by the teachers to say they

can't do iaido.

But the rules say they have to sit in seiza to pass an exam. Do they?

Looking through the book I see that you're supposed to sit seiza for

1-3 of Zen Ken Ren iai, and tate hiza for number 4. Looking through

some of the advice to judges I see it says we should refer to the book

so OK maybe. But I don't see anywhere that is says we cannot accomodate

disability. For a kyu test we forgive a lot of stuff that isn't "in the

book", we don't require the precision we require for a 5dan... perhaps

we should, if what the book says is iaido, what kyu challengers do

isn't iaido so perhaps they should fail. They don't, we accomodate.

As for the grading standards of each country, well there we have it.

There is nothing in the CKF grading policy that says we can not

accomodate bad knees or other problems. What is not specifically

forbidden falls under the jurisdiction of the chief examiner, so the

bottom line comes down to what he says. If the chief examiner says it's

fine to accomodate in a grading, it's fine. If he says no, you don't

pass if you do your seiza techniques while standing. The head judge at

any particular grading can give direction on any such grey areas to the

panel in his pre-grading talk. On this topic though, it's pretty cut

and dried, you pass or fail by doing seiza or not, so unless the

organization needs the test fee money, the chief examiner should make a

public decision and then those who can't sit seiza will not be allowed

to challenge a grade. It's pretty simple. Now, to my mind, if the chief

examiner does not forbid, head judges should also not forbid. In the

absence of a negative decision, accomodation should be made.

No matter what, however, the head judge does not get to review or

change the decisions of the panel, and it comes down to each judge. If

the majority of judges want to fail someone for standing rather than

sitting, it's a fail. If they decide to pass even if the head judge

says they must fail.... well the student should pass but the head judge

will have some things to say to the panel.

But people will cheat and not sit in seiza to make it easier to pass or

win a tournament. Really? Do we mistrust our students? For what reason?

If they "cheat" in a tournament what do they gain? Not money, not

lands, not fame and fortune. About the worst we can say is that it's

not fair to the opponent. But when I could sit seiza (and I cannot...

no, will not... now) I had no more trouble doing the kata than when I

stood. To make someone with bad knees sit seiza against a person who

has good knees is more fair? Not in my opinion. Stand the bad knees up

and judge the iaido not the health of the competitor's knees.

Same goes for gradings, judge the iaido, not the knees, or the nerve

damage, or the stroke, or the missing limb (all of which we have taken

into account in the past). And as far as someone passing a grading

without seiza, what harm is that to the art if their iai is good and

their teaching skills are unimpaired? What harm to the organization?

None at all, in fact it's more fees into the bank account!

So what does Japan do? Ah, the ultimate argument yes? Well Japan allows

for disability with a doctor's note, and the disability is noted on the

grading sheets available to the panel. While this seems a good idea,

and it obviously works for Japan, there are some things to consider in

the West. First, we don't have huge numbers of anonymous students lined

up in front of us. It's pretty clear to us who has a problem without

consulting doctors. Next, not all people have access to doctors notes

for free, and remember these notes must be obtained for every test.

Health changes from test to test. Who puts all this medical information

on the grading sheets? It has to go in there before the grading? And a

doctor's note? "Hey doc give me a note that says I can't fold my legs

past the place where you would consider it smart to fold them and then

drop my entire body weight onto them" ..... "umm OK". What's the note

prove?

Bottom line, it's no big deal not to grade in iaido, so the

organization should decide whether accomodation is allowed or not, and

then put a mechanism in place to accomodate if it does. My favourite

mechanism is "benefit of the doubt" where I assume if someone is not in

seiza there's a reason for that beyond "I'm tired and don't feel like

it". I can usually tell if they've got knee problems anyway, they look

like they have knee problems. So grade or don't grade, simple one.

What about practicing iaido at all? Well that's up to the instructor

and all the points above are relevent. Here's one final: Folks should

be tough, it's a martial art after all.

When I was young I believed this. I was tough, I used to exercise until

I threw up, I did Aikido with dislocated shoulders, I did Tae Kwon Do

with broken fingers, I played football with damaged knees. I still do

very stupid things in a similar manner but now it takes me years

instead of months or weeks to recover and it never comes back all the

way. It Never Did, but I didn't know that.

My point is that it is unfair to a student's future life for us to

demand they try to do seiza when they can't or shouldn't. Broken knees

mean a poor old age. Replaced knees do NOT bend to seiza. We are not

allowed to ask people to sacrifice their future independance for what

amounts to our amusement. In fact, as one of the damaged, supposedly

smarter, certainly older, folks who have "gone before" I figure it's my

job to watch my young students and when they start to do something that

might damage their old age say "get off your damned knees and do it

standing!"

But that's just me.

|

April 9, 2013

|

Teaching

|

Who Gets to be

Sensei

A senior in one of my arts said: "Amazing how 'You guys are welcome to

practice on your own with what you have learned' can be translated as

'you are the leader of your group!'"

But that IS a certification, you may as well put it in writing and give

it a fancy name... and charge money for it. You say "go practice" or

"go teach" and you've certified that person to do something. You can't get away from it.

The only thing to be done with students who want to be teachers is to

take up the Groucho Marx theory. "Any club that would have me as a

member, I don't want to join". In other words (and to twist the hell

out of it) if the students want a rank, give them a great big whopping

one and say "OK you've got it all, go away and teach". Then get down to

practicing with the ones who don't give a crap for rank.

There's really only one (sometimes two) grades in any martial art

anyway. The first is "you can teach" and the (sometimes) second is "you

can tell people they can teach". The rank that says "you own the art"

isn't really a rank, soke isn't really something to be challenged and

earned like the other ranks.

This goes for the "gendai" arts as well as the "koryu" whether they

have formal certificates or not, there are two levels that mean

anything. Yes these can be split to finer distinctions (like teaching

beginners and sitting a grading only up to X rank) but they are degrees

of the same thing.

Lessee, I have no formal (but teaching) rank in 3 koryu and teaching

rank in 3 gendai (all formal) and grading rank in 2 gendai. That make

me anything I wasn't yesterday? That get me any more students than

yesterday? Rank has little meaning to me, never have really needed it